Along with being the first episode in a possible series of essays, this is also the first essay I’ve ever written in English and decided to publish here. Although I occasionally jot down notes, verses, and thoughts in English—mostly about things I’m reluctant to write about in my native tongue—I never intended to publish them. However, I see Substack as a kind of training ground, a way to master the language I aim to perfect.

I could probably write an entire essay on why I primarily write in Croatian, but for now, I’ll simply say that my new employers are real Americans (I’m not writing for machines), I feel it’s essential to hone my writing skills in this language as well. That’s why this essay—about a song and a woman I love—is in English. And I’ll keep calling it an essay, even though I’m not entirely sure that’s what it is.

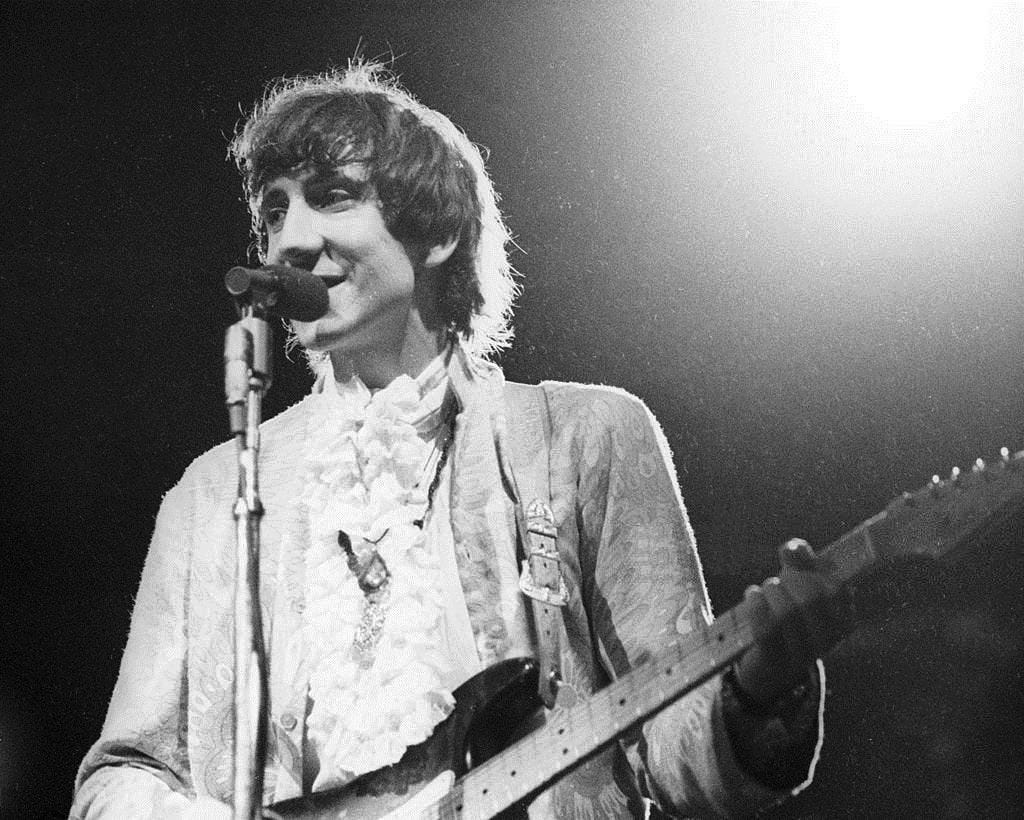

The Who was one of my earliest favorite bands. I first encountered their music in the 2003 film School of Rock, one of the most influential movies of my life—and a strong contender for episode one in a series of essays about those. I mention this because I want to make it clear that my love for the band wasn’t sparked by CSI. (I was always more of a Midsomer Murders girl.)

Pictures of Lily, released as a single in 1967, is one of my all-time favorite tracks by The Who. I wish I could remember the first time I heard it, but I can’t. Still, I have a strong sense that what I feel when I listen to it today is an echo of that first experience. I’ll walk you through the song and highlight the moments that make it one of the most moving masturbation songs ever written.

PICTURES OF LILY

(written by Pete Townshend)

I used to wake up in the morning

I used to feel so bad

I got so sick of having sleepless nights

I went and told my dad

He said, “Son, now, here's some little somethings”

And stuck them on my wall

And now my nights ain't quite so lonely

In fact I, I don't feel bad at all

The kid can’t sleep and decides to talk to his dad about it. Instead of an advice, he gets some “dirty” pictures for his wall. I hope you caught the reference to masturbation, because many radio stations in the 1960s didn’t. Maybe the chorus and bridge will make it clearer:

Pictures of Lily made my life so wonderful

Pictures of Lily helped me sleep at night

Pictures of Lily solved my childhood problems

Pictures of Lily helped me feel alright

Pictures of Lily

Lily, oh Lily

Lily, oh Lily

Pictures of Lily

Nowadays, this power pop song sounds pretty innocent. However, it was eventually banned by several broadcasters, and Pete Townshend, the songwriter, had to defend it against accusations of pornographic lyrics.

I was surprised to learn that this was the first song to be described as “power pop”—a term Townshend used in an interview with NME’s Keith Altham. Apparently, he coined it to describe not just his own band’s sound but also the early music of Small Faces and the Beach Boys. Later, power pop came to define a genre that sought to revive the early Beatles sound—catchy tunes with attitude, contagious harmonies, and jangly guitars—pop music with a punch.

The French horn solo in the middle of the song was an attempt to emulate a World War I klaxon warning siren. Why? I will explain shortly.

Here comes my favorite part:

And then one day, things weren't quite so fine

I fell in love with Lily

I asked my dad where Lily I could find

He said, “Son, now don't be silly

She's been dead since 1929”

Oh, how I cried that night

If only I'd been born in Lily's time

It would have been alright

My favorite part was the one where the father tells his son that the girl he fell in love with is dead. No wonder I became a fan of Neutral Milk Hotel a few years later.

As a contributor to the genius.com noted, the trauma of the father’s revelation doesn’t seem to shake our hero’s infatuation. His imaginary relationship lives on.

Pictures of Lily made my life so wonderful

Pictures of Lily helped me sleep at night

For me and Lily are together in my dreams

And I ask you, “Hey mister, have you ever seen

Pictures of Lily?”

Now, I wasn't a boy, but I was curious—and I wanted to see pictures of Lily.

So, who was she?

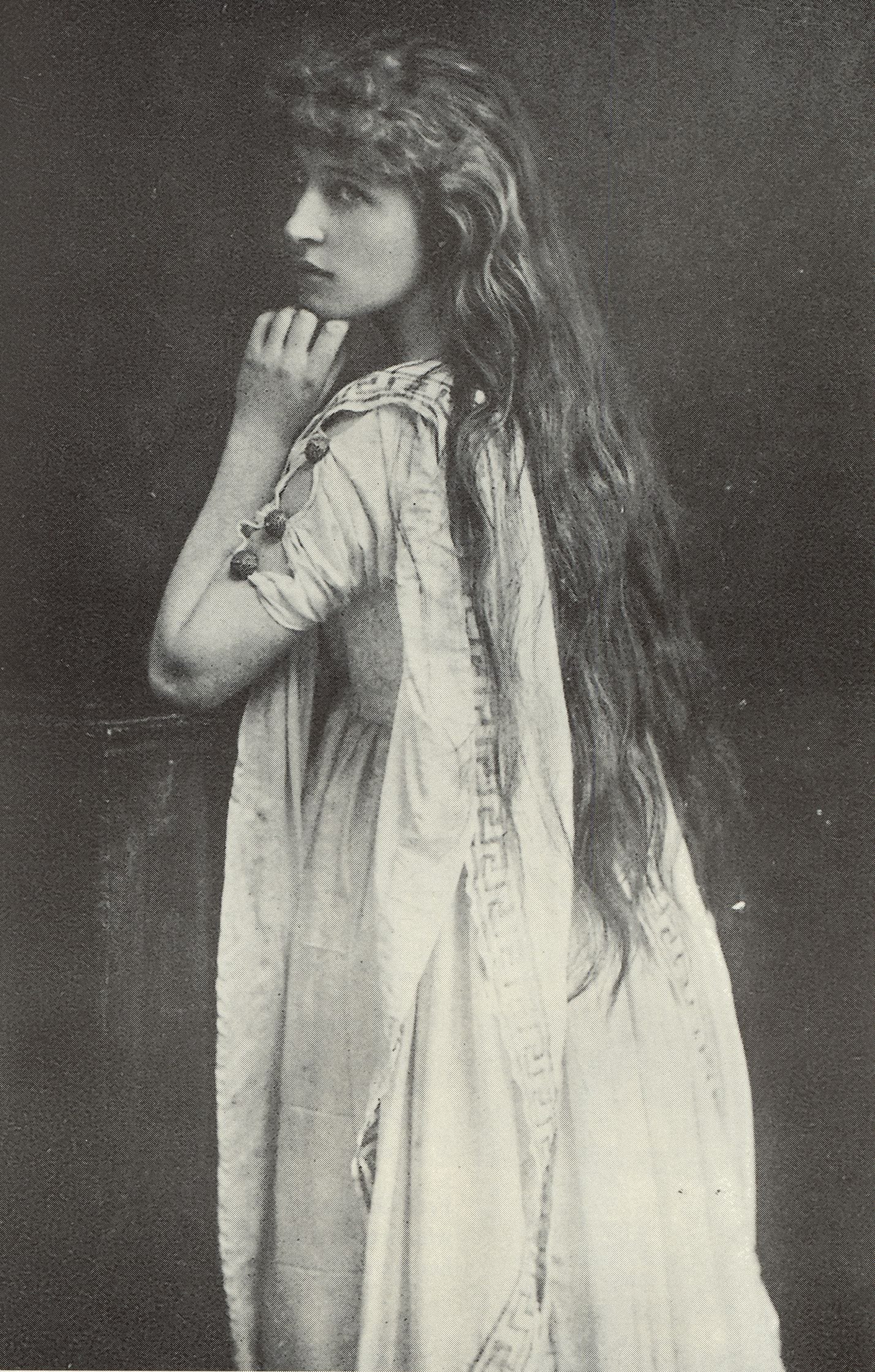

Apparently, the inspiration for the song came from a picture Pete’s girlfriend had on her wall of an old vaudeville star—Lily Bayliss. That, it seems, also explains the French horn mimicking a World War I warning siren, as the Lily in question was a World War I-era pinup.

“It was an old 1920s postcard, and someone had written on it—'Here’s another picture of Lily—hope you haven’t got this one.' It made me think that everyone has a pin-up period,” Pete said in a 1967 interview (the one I mentioned earlier).

However, my research from nearly twenty years ago suggests otherwise. Many believe Pete simply mistook the Lilies. Given the year listed in the lyrics—1929—it’s assumed that the song was actually inspired by an English actress, Lillie Langtry. And she was never a pin-up girl.

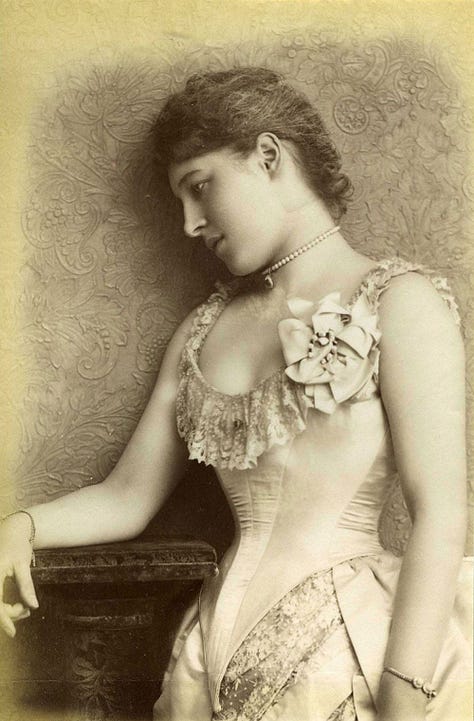

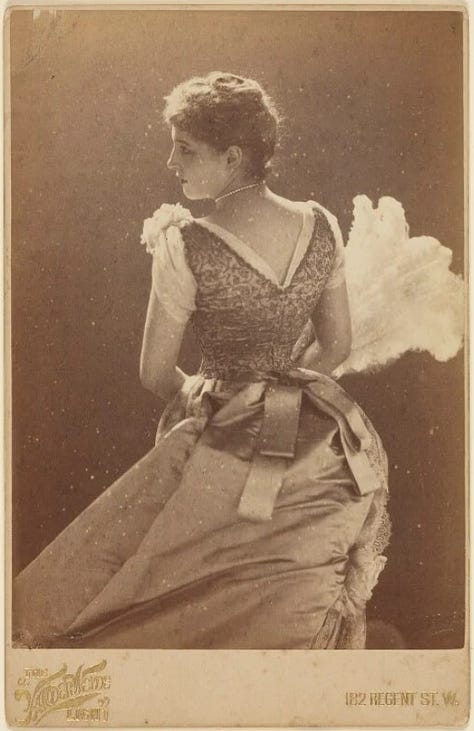

Nevertheless, she was stunning.

Lillie Langtry, née Emilie Charlotte Le Breton, nicknamed the Jersey Lily, was a British actress born on the island of Jersey in 1853.

“A dean’s daughter, a sister to six brothers, a wife to a wealthy merchant, an acknowledged beauty, a society A-lister, an artist’s model, mistress to a future king, inspirer of poetry and plays, and a society hostess,” says her biography. “Intelligent, humorous, and fascinating to both men and women, she was admired and idolized by people from all walks of life. Envied, respected, adored and lampooned. A controversial figure who challenged Victorian society’s attitudes toward women, but was no suffragette.”

Her life was the stuff of gossip and soap operas—royal affairs, bankruptcies, theater, literal soap commercials, and horse races. Yet, despite the drama, she managed to build a successful career as a critically and publicly acclaimed actress and entrepreneur, demonstrating a remarkable level of independence.

“I resent Mrs. Langtry; she has no right to be intelligent, daring, and independent, as well as lovely, ” said Irish playwright and critic George Bernard Shaw.

“I would rather have discovered Lillie Langtry than America,” said another Irish author, Oscar Wilde, who also paraded the streets with bunches of lilies, proclaiming that he was going to meet the new Helen of Troy. He even wrote a song about it—The New Helen—and later penned Lady Windermere’s Fan for her.

No doubt about it—pictures, as well as paintings of Lily, were above the beds of many men for years after the end of the Victorian and Edwardian eras.

After conquering London, she did the same in New York—then inspired someone to name a town in Texas after her.

She made one movie, His Neighbor's Wife (1913), and spent her twilight years in Monaco at her cliff-top villa, Le Lys, with her garden as her pride and joy. They say her autobiography The Days I Knew (1925) revealed more through what she left out than what she included.

When she died, newspaper headlines proclaimed the end of an era.

She's been dead since 1929.

This brings us back to 1967, when the Who’s song came out. And early 2000s when I first heard it.

I find it hard to explain why certain songs move me, and this one is no different. But I can attest that this little ditty opened up an entire world for me, and the effect was only slightly connected to the original intent of the author—assuming he was honest when he described Pictures of Lily as, “merely a ditty about masturbation and the importance of it to a young man.”

Perhaps I was curious, perhaps morbid, but as a young girl, I saw much more in this song. To me, it will always be a song about the lasting legacy of Lily Langtry’s beauty.

In the foreword to her autobiography, the English poet Richard Le Gallienne describes Lily as the representative of Beauty in her time, which, according to him, “is nearest to the fame of gods, for the fame of Beauty is the fame of a miracle and belongs to the supernatural. He goes on to say, “It is such a book as Helen of Troy might have written—if she only had possessed Mrs. Langtry’s sense of humor,” adding that “if Helen had possessed humour there might have been no Trojan war.”

It’s interesting that, in a time when every woman has ways to enhance her beauty, we seldom speak of beauty in this way. Even now, when I mention her name and her beauty, it’s in the context of the so-called “dirty pictures” and cheap pinups.

Of course, her first name, actually a nickname, also carries significant meaning. Any Oscar Wilde fan should take note of that! It subtly hints that the song is ultimately about the loss of innocence, much like Townshend’s conversation about masturbation as a rite of passage implies.

The lily, in Christian symbolism, represents virginity, purity, and chastity, and is also associated with resurrection. In Folklore and Symbolism of Flowers, Plants and Trees, Ernst and Johanna Lehner write that, as an ancient Semitic legend tells it, the lily sprang from the tears of Eve when, upon being expelled from the Garden of Eden, she realized she was approaching motherhood.

The lily has long symbolized motherhood in many traditions, yet this story is just as much about the sorrow of innocence lost. In this sense, Pictures of Lily mirrors the story of Eve, as both represent a transition from innocence to experience—marking a passage from one phase of life to another; filled with discovery, loss, and growth.

I have yet to read the autobiography of the fabulous Jersey Lily, but I can safely assume she also lost her innocence somewhere along the way.

In conclusion, I have nothing more to add, but I do ask you this:

Hey mister, have you ever seen pictures of Lily?